Embedded in our current moment is the unique opportunity to interrogate the manner in which we conceive of what it means to read. A materiality that was once self-evident – i.e., you read a book, or a sign, or a magazine – in the relationship between a text and the act of reading has receded into the ephemeral cloud of digital storage and display. Engagement with a text, and indeed any solid definition of what constitutes a text, has been uprooted and made unstable by the advent of digital readers, word processors and computer screens. Certainly this is no original claim, and it has been made more incisively and eloquently, but it bears keeping in mind when encountering Erica Baum’s Dog Ear.

In Baum’s introduction Kenneth Goldsmith traces a portion of the poetic genealogy of Dog Ear – in Pound’s “radiant node(s)â€, Burroughs’ Fold-ins and Porter’s Founds – and expresses the precarious position of the dog ear as physical bi-product of the reading process, that being “[contingent] upon the de/formation of a physical page, the dog ear’s obsolescence was assured in the digital age†(iii). Goldsmith also gestures toward the obliquely digital process by which one may read Baum’s plates, by having at least two paths to take through each text, relating their leonine-like structure to a sort of precursor to hypertext. For Goldsmith this process articulates current tensions in any definition of reading, stating that, “For Baum, the act of reading is up for grabs … What is the best path?†(iv). The end result of Goldsmith’s line of inquiry is the conclusion that Baum, “[by] spotlighting the way language describes information systems in analog media … makes us aware of how that same language is used in computing … the language our operating systems employ comes from a pre-digital age – desktops, folders, web pages†(vii – viii).

Beatrice Gross, in her essay that follows Baum’s plates, picks up a thread that Goldsmith alludes to briefly in his introduction, that Baum “has selected these dog ears equally for their visual and literary merits†(vii). Gross explicates the manner in which the conception of these pieces, as equally visual and literary, obfuscates the divide between these two traditionally disparate realms, stating that “Baum’s dog ears make signifier and signified coincide perfectly in one fold, drawing our attention simultaneously to their visual and linguistic features†(64). This simultaneity, for Gross, has resonance in the piece’s engagement with form and content as well, stating that Baum’s “printed landscapes – where found verses and embodied geometry conspire to create a nagging unity of matter and meaning – expose the irrelevance of the disjunction between form and content … the photographs allegorize their very inseparability†(68).

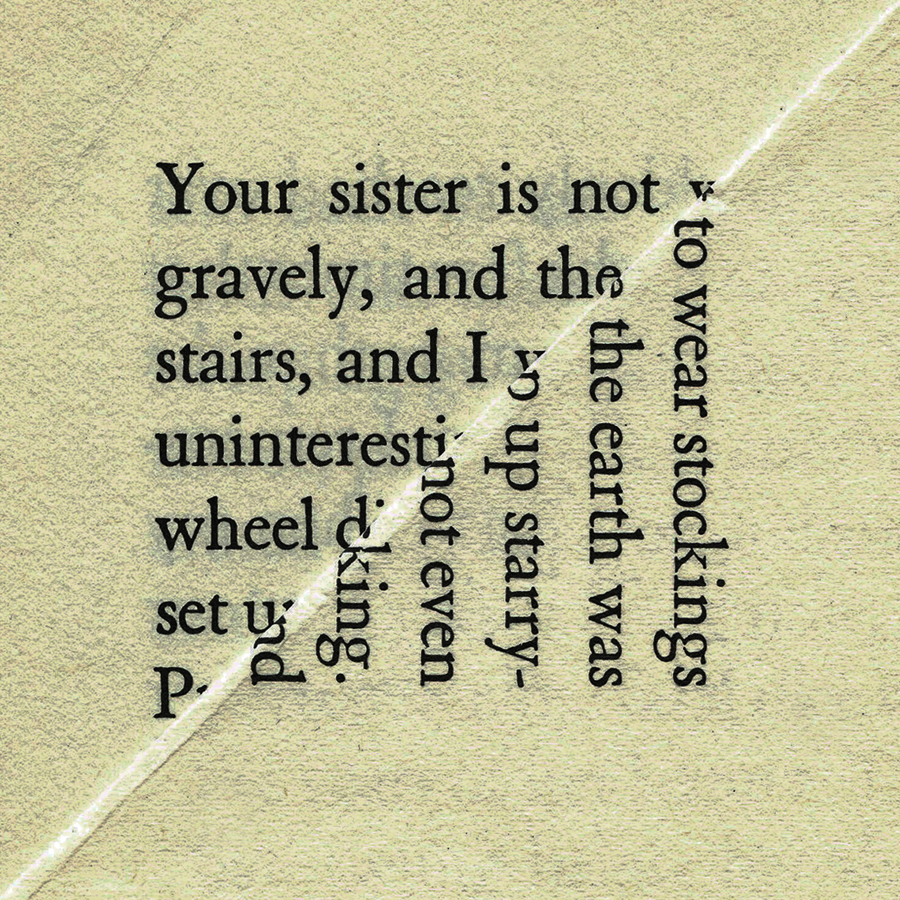

Beyond the salient points regarding Dog Ear‘s visual and literary merits put forward by Goldsmith and Gross, Baum’s work engages and reconfigures the traditional mode of reading poetry. The visual structure of the poems make explicit the poetic convention of “the turnâ€; what was once an implicit gesture of expression here becomes physically manifest in the right-angled turn of the phrase to move down the page (should one choose to read the poems around the fold). A plate such as “Not to Wear Stockings†may read, “Your sister is not [] to wear stockings / gravely, and the [] the earth was / stairsâ€, the right turn actualizing, on the page, an internal turn of the line not unlike the blank space of a caesura. Gross’s assertion that the work refutes dissection into its literary and visual components proves to be true through this marriage of poetic convention and structure.

By non-prescriptively presenting texts that are open to multiple paths of reading Baum’s plates expose an instability lurking beneath any encounter with a text: a choice, whether actively or passively made by the reader, determines how the content of a text is to be consumed. How any reader navigates a single text, involves decisions on how to manage the information given by the text. This process of information management exists implicitly in reading traditional modes of writing, in consuming the content on a physical page, but is made more visible in the digital age, wherein information is leveled and made more malleable by its digital composition. The beauty and grace of Baum’s work is in its simple and elegant conception, regarding a traditional mode of reading/manipulating a text – the dog ear – with an eye to the contemporary age. Baum’s awareness reveals how, as Goldsmith asserts, new technologies are in direct dialogue with, and are reliant on, previous modes of creation and reading.

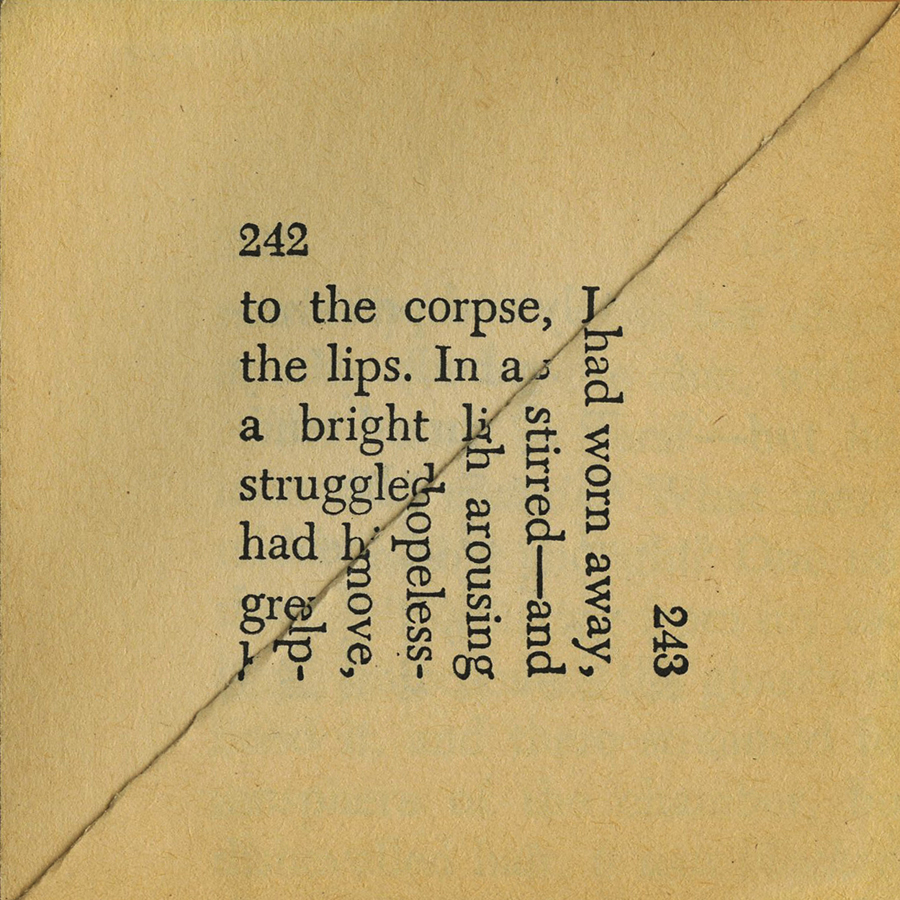

Beyond its concept, the poetry of Dog Ear acquits itself well, which is a testament to both Baum’s concept and her curation skills. A poem such as “Corpse†reads evocatively as both

to the corpse I had worn awaythe lips In a stirred anda bright arousingstruggle hopelesshad move

or

to the corpse Ithe lips In aa brightstrugglehadhad worn awaystirred andarousinghopelessmove

In each case the poem generated by the path of reading loosely gestures toward a similar theme, but with subtle and strong differences. The second reading introduces a closeness the corpse that does not exist in the first; in the first reading the speaker identifies with the corpse as either their own or a corpse that they have acted on, “to the corpse I had worn awayâ€, whereas the second posits the speaker as the lips of the corpse, “to the corpse I / the lips In a / a bright / struggleâ€. The movement between these two positions is a subtle but powerful movement which alters the sympathy of the reader considerably.Baum’s texts, however, actually present themselves in a less clearly delineated manner than this streamlined reading; half-words and solitary letters scatter along the fold, disappearing beneath the surface of the overturned page. What could be construed as a problematic element to the reading process, incomplete words resulting in fractured semantic meaning-making, allows Baum’s work to both visually and literally account for the incompleteness inherent in any text. This fragmented condition also offers an invitation for the reader to complete the hanging words and phrases, further moving the relation of the reader to the text away from passive receptiveness toward a more active role in the generation of its meaning. The reader is free to generate and substitute words that the fragments on the page allude to. Baum’s poems exist in a quantum state, vacillating between any infinite number of readings when completed by the activity of the reader.

The instability of the text proves itself to be somewhat of a misnomer in Baum’s plates. The poems present themselves equally visually and textually, open themselves to be read in many different manners that engage the reader actively in a non-prescriptive manner. Baum’s work stands not as a mortified text nostalgic for the prematurely buried artifact of the book, but rather as an inclusive and generative gesture that illuminates the genealogy of contemporary engagements with writing.

———-

没有评论:

发表评论